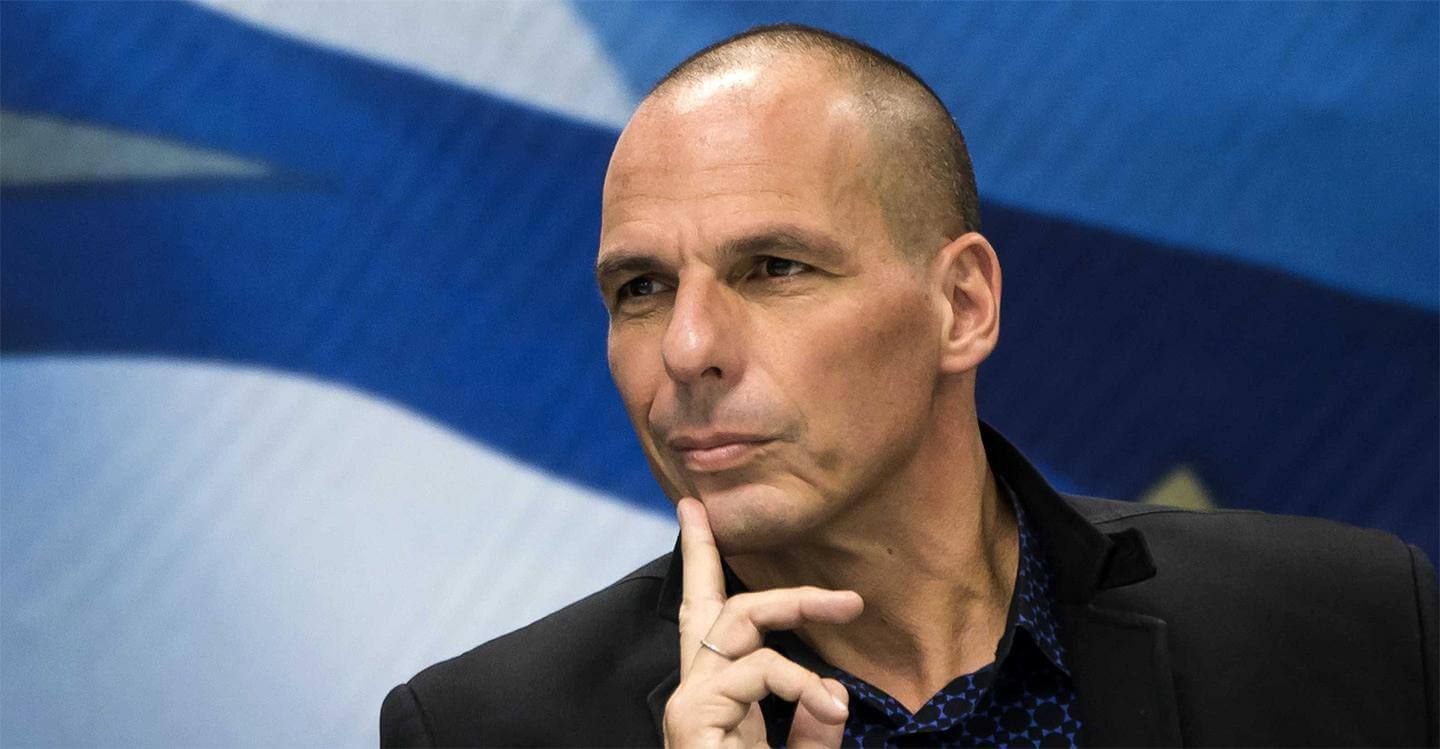

The new finance minister of Greece is a flamboyant economics professor that, until very recently, you had probably never heard of. Thanks to his European showcase these past few days, some extravagant -and sometimes contradicting- proclamations and his undeniable personal charisma, he has become a star in global news headlines. There are fake Twitter accounts and ironic Tumblrs about Yanis Varoufakis.

But what is he smiling about?

Unlike his German counterpart, Yanis Varoufakis had chosen to read from a prepared statement, which was unusual. This meeting, his first with Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, was crucial, but wasn’t expected to generate substantial results. Indeed, it didn’t -Varoufakis didn’t even agree that the two men agreed to disagree. They would therefore have nothing particularly poignant to share, and the focus would lie in the mood implied by their general statements. And many people were watching.

Five years after Greece’s economy collapsed, and less than two weeks after Greeks elected a radical left party to govern, the relations between Greece and Germany could be described as tense at best. The new Greek government has rejected the previous austerity program agreed upon by the former government and the country’s debtors, and now considers the negotiation of a new program and an additional restructuring of its mountainous debt to be its clear mandate. This has sent shockwaves across Europe and the markets, raising doubts about the new government’s ability to convince its European allies to rethink or renegotiate anything. That is why Varoufakis was in Berlin on Thursday morning, the culmination of an urgent European tour. He wanted to explain his positions, and set the tone for deliberations to come. To be there, in Berlin, he’d miss the swearing-in ceremony of the new parliament back home in Athens.

Next to the frail 72 year-old Schäuble, the tanned, lithe Varoufakis seemed younger than his 53 years. He began reading his prepared statement and, soon after, right there, in the heart of Berlin, next to a man who has been a member of the Bundestag since 1972, Varoufakis started talking about Nazis.

—

Yanis Varoufakis is an economist. The main focus of his work has always been game theory, the study of strategic decision making. Born in Athens on March 24, 1961, he studied mathematics, statistics and economics at the University of Essex in the UK and, after a fellowship at Cambridge, moved to Australia to teach at the University of Sydney. He spent eleven years there, became an Australian citizen, got married, settled down and then, somehow, as so many expats eventually do, he decided to return to Greece. He taught Economic Theory at the University of Athens, created a lauded post-graduate program there, and produced some interesting work, including two well received books, “Foundations of Economics: A beginner’s companion” (2002) and his best known work, “Game Theory: A Critical Introduction” (2004). As a scientist he is well respected by his peers, despite the fact that he has held somewhat controversial views, questioning fundamental tenets of economic theory. His colleagues at the time describe him as inquisitive and cordial. “His post-graduate program was a noteworthy achievement”, says professor at the University of Athens Aristides Hatzis. “It focused on both theory and methodology, and was something sorely missing from Greece at the time. Varoufakis came in and built it. It did wonderful work”. “He was a very energetic teacher”, says Thodoris Papageorgiou, a student of Varoufakis in the early ‘00s. “He encouraged discussion on his subjects, and was extremely approachable and open. He’d write his mobile phone number on the board, for anyone to use”.

Around that time Varoufakis also produced something else: His daughter, Xenia, was born in 2004. One year later, however, he and his wife separated, and she returned to Australia with Xenia. Varoufakis chose to stay. He met conceptual artist Danae Stratou, a divorced mother of two, and scion of an industrial family, at a private event, and they instantly fell in love. In 2005 as part of her research for one of her works, they journeyed together to several countries with disputed borders, from Eritrea to Palestine and from Kashmir to Ireland. They married, and are still together.

Varoufakis stayed at the University of Athens until 2012, when he took a leave and went to work for Valve Corp., a quirky video game company in Seattle. As “economist-in-residence” at Valve, he conducted research on exchange rates and trade deficits in virtual economies. After a few months there, he went on to teach at the University of Texas at Austin.

What this career path shows, quite clearly, is this: Yanis Varoufakis is not a politician. Despite his adventurous nature, he has never been anything but an academic. How did he end up in the heart of Europe’s most challenging political negotiation? That is an interesting story as well. It is a story about a blog, a summer house and an ambitious fixation.

—

Some politicians tend to surround themselves with intelligent people, or seek out the counsel of expert advisors. That means that most successful Greek academics who work in fields adjacent to politics (economics, political science), are eventually summoned to consult or interact in some other meaningful way with the political class. Varoufakis had been an advisor to George Papandreou from 2004 to 2006, during Papandreou’s first years as the leader of centre-left PASOK. He left disappointed and disillusioned, and has been pretty vocal against Papandreou’s lack of organisational skills or strategical thinking ever since. One would expect that he wouldn’t have anything to do with politics again after that experience, but then something else happened:

The Greek economy imploded.

In 2010 George Papandreou, now a Prime Minister, announced that the country would seek a bailout from the EU, the IMF and the ECB. This cataclysmic event had violent repercussions throughout Europe, and led to the massive €240 billion bailout and a wave of austerity measures that have put enormous pressure on Greek taxpayers and have led to a radical overhaul of the Greek political system. Another result of the crisis: Yanis Varoufakis started to blog.

From March 30, 2010 until December 16, 2014, Varoufakis published 263 blog posts on protagon.gr, an opinion portal launched by journalist Stavros Theodorakis (who, fun fact, would go on to found a political party called “To Potami”, that would elect 17 MPs this January), as well as dozens of other posts and notes on his personal blog, where he mostly writes in English. The vast majority of his articles were about the details of the crisis, analysis of what the major players (the Greek government, the IMF, the ECB, Germany) were doing, and Varoufakis’ opinions on what they should be doing. Written in a concise, authoritative but immensely accessible manner, his posts started garnering attention, and he started to get noticed by an audience much wider than his fellow economists. Before long, invitations to appear on talk shows started coming in, and those appearances introduced him to an even larger audience. Here was a guy who spoke in a clear, authoritative voice, who looked good on TV, smiled often, and seemed to know what he was talking about. He was an instant hit. His articles on Protagon and weekly free-press newspaper Lifo were widely read, his Twitter followers were multiplying rapidly.

The underlying theme of Yanis Varoufakis’ blogging was his masterplan. His ideas about the European financial and monetary crisis, and his proposals for its solution had been assembled in a paper called “A Modest Proposal For Overcoming The Euro Crisis” (2011). The paper is co-authored by economist Stuart Holland, and describes a plan to essentially absorb part of the weaker European nations’ debt into the EU itself. The plan calls for a stronger fiscal Union, in which money from surplus-states is redistributed towards the deficit-laden states, not as debt relief, but as investment for recovery and growth.

Over the past few years Varoufakis has explained, refined and detailed this plan multiple times in his blog posts, and has evolved it to include -or, rather, to begin with- the Greek debt restructuring. He maintains that the Greek debt is not viable and should be restructured in a way that should become standard procedure for the European Union. He wants Europe to use Greece as a launching pad for the kind of Eurozone-wide fiscal reform he proposes.

His idea was met with scepticism by some of his peers, who observed his prolific output (he sometimes posted two or even three long, elaborate articles per week) with caution and, as one colleague of his told me “some bewilderment”. But his mainstream readership continued to widen, and would soon grow to include a nascent, increasingly powerful political movement. Even before the election of 2012, Varoufakis’ ideas about the debt restructuring and the European crisis had become a central part of SYRIZA’s political platform.

—

Alexis Tsipras, the Prime Minister of Greece, owes his current status in large part to his mentor, Alekos Flabouraris. A friend of Tsipras’ father, Flabouraris was one of the people who promoted Tsipras within the party of Synaspismos (later to be renamed to SYRIZA), and helped him get elected party leader in 2008. Flabouraris frequently hosts Tsipras and his family at his summer house in the island of Aegina. Guess who else has a summer house in Aegina: Danae Stratou. The Tsipras’ and the Varoufakis’ families have spent at least one summer vacation together in Aegina, their children playing, the grown-ups talking about Greece and the future. In Varoufakis, Tsipras has found a prominent, independent voice who supports a message that is in line with his party’s populist platform: The Greek problem can be solved with a wider, European solution, and the austerity measures should be terminated immediately. SYRIZA, which originally had a rather one-sided populist anti-Troika platform, added Varoufakis’ debt-restructuring as one of its major political proposals, and Varoufakis came closer to the party, without ever assuming an institutional role. He blogged his support to SYRIZA in 2012 and the European election of 2014, but refused to be a candidate in either election, quite vehemently.

In 2015, however, things changed.

This time there was more at stake than a seat in Parliament, European or Athenian. This time SYRIZA had a clear chance to form a government, and Varoufakis could get his chance to negotiate his plan himself, with the policy makers of Europe. How many economists have an opportunity like this? This particular one wasn’t going to let it get away.

—

Sitting next to Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Yanis Varoufakis proclaimed: “We will not negotiate with the troika”. Talking to the Financial Times, he said that the government “would no longer call for a write-off of Greece’s €315bn foreign debt”, but opt for a “menu of debt swaps” to ease the burden. Speaking to the New York Times, he said that Greece “does not want” the remaining €7 billion loan disbursement from the current program, but rather to rethink the program. In Thursday’s press conference in Berlin, he said that “60% – 70%” of the reforms included in this current program are indeed necessary, and that Greece needs a “bridge program” to give her time to negotiate a new deal with her creditors. This was after he talked about the Nazis. “When I return home tonight”, he’d said, “I will find a country where the third-largest party is not a neo-Nazi party, but a Nazi party”. Supposedly the goal there was to strike a chord with the Germans, a people that found itself in what in his opinion were similar circumstances more than 80 years ago. Whether this approach proves tone-deaf or brilliant, it remains to be seen. However, Varoufakis’ entire strategy seems haphazard and made-up-along-the-way, appearing adamant and confident on one meeting, then emollient and conciliatory in the next. It is still early in the process, of course, and at this point there is still overwhelming support and goodwill towards the first initiatives of the new government, but the first round of criticism focuses on three things (four, if you count Varoufakis’ fashion choices): He is not a politician, his plan is focusing on the wrong things, and his narcissism could become a problem.

“The debt and its viability is not the most important issue”, a veteran politician told me. “Varoufakis and the government are focusing on the wrong thing”. There was a general expectation that Greece’s debt would be restructured sooner or later by any government. According to some, a Greek government should instead focus on making sure the country has access to capital, and implement sweeping reforms as soon as possible to kick start the economy. SYRIZA’s mandate is different, however, and Varoufakis is going to have to convince Greece’s lenders to renegotiate at least some of the party’s pre-election promises.

Varoufakis, a self-proclaimed “liberal marxist”, is not a member of the party nomenklatura. He has gained considerable clout by being elected MP with the most votes than anyone in the 300-member parliament this January (he got 137.000 votes in the 2nd electoral district in Athens, the largest electoral district in Europe), and he has the unconditional trust of the party’s leader, something very important in a political group that comprises of so many communists. But he clearly is not one of them. “If he fails to deliver a deal that is satisfactory”, the veteran politician told me, “SYRIZA will have an ideal fall guy”.

And there are questions about some controversial personality traits. The “n-word” cropped up very frequently in my discussions with people who have worked with him, though usually with disclaimers or caveats. Varoufakis was described to me as a mild narcissist, a man who is kind, has empathy towards others, but does love the sound of his voice a little too much, and thrives in the limelight. “Economics professor, quietly writing obscure academic texts for years, until thrust onto the public scene by Europe’s inane handling of an inevitable crisis” he muses lyrically in his Twitter bio. His bio at Protagon reads “He considers his highest accomplishment the fact that the Australian government had to pass an amendment to force the state radio station to cancel his weekly show”, referring to an incident that got him suspended from SBS-radio for “the promotion of negative stereotypes about Jews”. He even spells his name incorrectly, with one “n” (correct spelling of Yannis in Greek uses two), “for aesthetic reasons”. He is clearly a man who spends time thinking about himself.

Still, he may very well be the man for this, particular job. He is undeniably brilliant, he knows his stuff, and there are few people in Greece who can match his grasp of economic theory, his mastery of the english language and his (perhaps standoffish, but popular) innate swagger. And there are two other important factors to consider, both of which have been mentioned above.

First, it’s his “modest proposal” he is negotiating. He is a theoretical economist with a plan, and he has a once-in-a-lifetime chance to turn even a small part of it into political action.

And the second thing? Well, it’s a negotiation. Remember what his specialty is? Game theory. The study of strategic decision making.The Greeks are hoping that this is what Yanis Varoufakis’ perpetual smirk indicates:

He knows what he’s doing.

Originally published in Spanish in El Mundo.