There are several common themes defining recent Greek street protests: They invariably take place in Syntagma Square in Athens and on its adjacent streets. The communist bloc always marches separately from the rest of the protesters. The vast majority of the crowd consists of peaceful citizens, outraged by the continued austerity and lack of political guidance during what is turning out to be one of the worst financial disasters in the history of the modern world.

At some point, small groups of hooded anarchists attack the police with firebombs and rocks. The police respond by firing tear gas canisters indiscriminately into the crowd, dozens of them, trying to clear the area from everyone, violent anarchists and peaceful protesters alike. Brief battles ensue and, as the confrontations escalate, violence reigns. Storefronts are being broken into. Civilians are being struck and injured by way of baton, rock, police shield. Fires are being set on garbage cans, newsstands and cars. Sometimes even buildings burn.

And there is another common occurrence: A fierce old man is always in the thick of things, always front and center. But he is not a leader. He is prominent, certainly, but he is there as just another protester, older, yes, frail, but equally passionate. He always gets in trouble.

In March of 2010, he was tear-gassed by a riot policeman outside the parliament and had to be carried away to safety. This past Sunday, he was again tear gassed on pretty much the same spot, fainted, and had to be carried into the Parliament’s infirmary to get emergency assistance.

His name is Manolis Glezos. He has been fighting like this for seventy years.

One can note four major disruptive events in modern Greek history: The German occupation during World War II, the civil war, the military dictatorship and the financial collapse of the 2010s . Manolis Glezos has been involved in all of them.

The single event that would define Glezos happened very early in his life. Born in 1922 on the island of Naxos and raised in Athens, Glezos was too young to volunteer for the Greek Army when WWII began (an army that would eventually/surprisingly trounce the Italian invaders and then lose to the superior German Wehrmacht), so he enrolled in the University to study Economics.

On the night of May 30th, 1941, after the Germans had occupied Greece in its entirety (the last remaining bastion, the island of Crete, had just fallen), he sneaked to the top of the Acropolis hill through a cave, along with Lakis Santas, a friend and comrade. They managed to remove the Nazi flag from its pole by the Parthenon and sneak back down undetected by the guards. The symbolic value of their gesture was enormous: The news immediately travelled around the world and this simple act of defiance during one of the darkest periods of the war became a source of hope for embattled nations everywhere.

The two young men, unaware of the enormity of their act, hid the stolen flag in an ancient well (where it still lies today) and went into hiding themselves. They were eventually arrested about a year later. They were both nineteen years old, and were sentenced to death.

After the liberation, Lakis Santas would go on to become a communist, face prosecutions, and eventually emigrate to Canada and live the rest of his days in peace. Manolis Glezos, on the other hand, was only just starting the fight.

The end of the war did not bring an end to the suffering in Greece. The communist guerillas, who had been the most efficient and prominent resistance force against the occupying German Army, and the regular army of the new Greek republic would immediately begin a four-year civil war that would leave an already wounded country bitterly divided and ravaged. Manolis Glezos was a prominent member of the Communist Party and the editor of its official newspaper. As such, he was prosecuted and imprisoned on many occasions and for an extended period of time, long after the civil war had ended. He would get two death sentences for political offences, and would be elected to the Greek parliament while incarcerated. His sentences were never carried out, of course, and he was eventually released from prison in 1954. Four years later he was arrested again and was charged with treason along with other prominent members of the Communist party. He was sentenced to five years in prison and, while there, was again elected to the parliament. He was finally released in 1962 and remained free for another five years. He was arrested yet again on the first day of the 1967 military coup.

In total, he has spent almost sixteen years of his life in prison or in exile.

“Glezos is a symbol in the Greek collective consciousness”, says Nikos Marantzidis, a professor of political science at Macedonia University in Thessaloniki. “His revolutionary act during the war has become the defining moment of his career. But his political views were not constant. Glezos in the ‘5os was very different to Glezos in the ‘80s. If there is a constant in his career, it is the notion that Greece is a united nation that is always fighting against foreign enemies”.

In the ‘80s, Glezos, by now a member of a leftist political movement called “EDA”, participated in three elections as a candidate of PASOK, the socialist party led by Andreas Papandreou that would rule Greece for the better part of the ‘80s and would arguably lay the foundation for the wild accumulation of debt by a corrupt Greek state.

“During the ‘80s, the country developed a new narrative for the way it sees itself and the way it deals with its past”, says professor Nikos Marantzidis, “Glezos was very well positioned to become a focal point of this narrative”.

This may be an explanation to the remarkable and unprecedented staying power of Glezos as a political figure. Few others have managed to be present in all crucial moments of modern Greek history and play a pivotal role in those events. And while his ideology may have shifted to and fro along the way, what was always clear was this:

For Glezos, these were not separate battles. They’re the same battle. He is fighting it constantly.

The Greek financial crisis has now reached a crucial point. The past two years have been a constant barrage of austerity measures that have crippled the economy almost as totally as the citizen’s patience. As meaningful reforms prove painfully difficult and slow to implement, cuts in wages and pensions prove to be the easiest way to appease the country’s lenders in an ongoing negotiation that seems to be beyond the negotiating skills of this country’s political leadership.

The people inevitably take to the streets, and Manolis Glezos, along with his partner in outrage, 87 year-old legendary composer Mikis Theodorakis, is always there with them.

As it turns out, the narrative of the protests fits perfectly to his own.

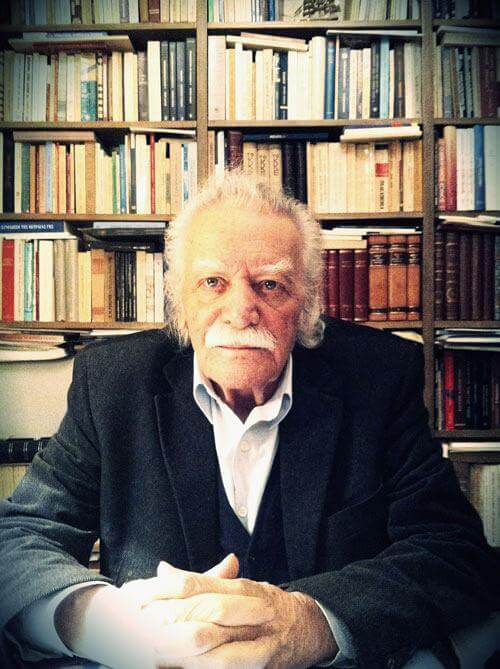

Manolis Glezos lives with his wife in an old two-story house in a northern suburb of Athens. He welcomes me into a study adjacent to the living room that is lined by books, photographs and memorabilia, familiar detritus of a full, active life.

Manolis Glezos lives with his wife in an old two-story house in a northern suburb of Athens. He welcomes me into a study adjacent to the living room that is lined by books, photographs and memorabilia, familiar detritus of a full, active life.

Glezos is an old man, but little about him hints that in September he will turn ninety. His elegant, austere face is crowned by a thick white mane of hair. There is a snow-white trimmed mustache above his lip and two bright blue eyes, ablaze with juvenile excitement and fervor set beneath two wild white brows.

His voice has a timber that is boisterous and clear –the voice of a politician or a demagogue, and a good one at that. He doesn’t look a day older than sixty. We talk about what all Greeks talk about: The financial crisis.

“The only solution right now is elections”, he says. “Everything has changed. Our political system is in disarray. The government is completely removed from the will of the people. We need elections, and we need the parties of the left to unite, to put their differences aside, and claim the chance to govern”.

According to a recent poll, this does not seem far-fetched. The three leftist parties currently in parliament (Democratic Left, SYRIZA and the Communists) would get a combined 43,5% of the vote, with right-wing current front-runner New Democracy scoring a paltry 27,5% (governing PASOK has collapsed to fifth place with 11%). The notion that those three parties could set aside decades-old differences and unite, however, does seem quite far-fetched indeed.

“If the Left loses this chance,”, says Glezos, “it should dissolve, let itself be cast aside”.

Glezos has a very clear set of ideas about the economy and the country’s future, and he is very adept at explaining them. He believes that Greece should refuse to pay any of its “odious” debt. He has a complete five-point plan to reform the Greek economy. He knows exactly what needs to be done for the rebirth of heavy industry in the country and has ideas for the restructuring of its energy infrastructure. And he believes that Greece must claim the reparations Germany owes it since the war.

“They need to give us what we are owed”, he says. “According to my calculations, the amount comes to about 162 billion euros. With a 3% interest, the amount goes up to over a trillion. Greece is the only country that hasn’t been paid the reperations it is owed. And Germany is the only country that hasn’t paid us. Bulgaria paid. Italy paid. We should talk about this seriously. Our governments have been stalling for decades. I have been fighting for this cause since 1946”.

Another constant in his career has been his belief in absolute democracy, the right of the people to govern themselves. As a mayor in his home village of Apiranthos, in Naxos, he developed a short-lived system of self-government in 1986. He envisions something similar for all nations.

“All power should belong to the people”, he says. “This is a change that cannot be stalled or stopped. We should all participate in the decision making process. Political power should be distributed among the members of a society”.

His lucidity and his eloquence are enchanting, his enthusiasm and his zest are infectious. One can dismiss some of his ideas as ramblings of an old man (some do), but no one can deny the power of what he represents, or the way he has used (and honored) his own symbolism for seventy long years. This, in itself, is an achievement on par with the removal of the Nazi flag from the Acropolis.

I ask what is it that drives him, what fuels his passion after all these decades of struggle.

“118 friends”, he says. “I lost one hundred and eighteen of my comrades. They were executed during the civil war. Back then, before each battle we said what we hoped to achieve, our dreams and our goals to each other, because we knew that not all of us would make it. We wanted to have the survivors carry out some of those dreams. I survived all those people.”

He raises himself from his desk and walks over to a painting on the wall. It is a gift from a German painter. It is a painting of his brother.

“My brother was three years younger than me”, he says, as his voice becomes coarse. “He was executed when he was nineteen years old. How can I forget him? He comes to me every once in a while. He asks me, how things are. If we’ve found solutions, done things. Are you doing anything Manolis, he asks, or are you filling up ashtrays with cigarette butts, just talking?”

“This is what I am fighting for”, says Manolis Glezos. “I am fighting for them”.

published on Cronica, a supplement of the Sunday edition of El Mundo, February 19, 2012

original text, submitted in English